|

| Some have speculated that the straight-pull action survived in Switzerland only because it was never tested in combat, but no one doubts its accuracy. |

|

| Note: This article first appeared in the May

10, 1999 issue of Shotgun News. It is reprinted here with permission.

All the text is as appeared in the original article. The black&white

photographs were provided courtesy of Man

at Arms Magazine/Mowbray Publishing. The color photographs were provided

by Big L.E.E.

By Paul Scarlata

When I lived in New York many years ago our neighbor was a doctor who

had immigrated from Switzerland shortly after World War II. Being avid

shooters, my brothers and I loved to question him about that mountainous

"nation of riflemen." He once told us a story which, while I cannot vouch

for its veracity, exemplifies the Switzer's pride in his citizen army.

The Swiss have always been a pragmatic people. They realized early on

that their traditional neutrality could only be maintained by making any

aggressor realize that the Swiss would offer massive resistance to an invader.

This was accomplished by maintaining the best trained and equipped "people's

army" in Europe.

Thus the Swiss were the first European nation to equip their entire army with a repeating rifle, the Gew. 1869 Vetterli--a bolt-action rifle with a 12-shot tubular magazine under the barrel. It was chambered for the 10.4x38 Swiss rimfire cartridge which, while not as ballistically impressive, gave the Swiss soldier an unprecedented rate of fire. And the Swiss soldier was a trained marksman. Marksmanship was constantly stressed and the government subsidized target shooting among reservists and civilians to encourage proficiency with the rifle. But by the 1880s it had become apparent that the Vetterli rifle was quickly becoming obsolete. The Swiss were fortunate in having one of Europe's foremost proponents of smallbore jacketed bullets in their army. In 1881 Major, later Colonel, Eduard Rubin, the director of the state munitions factory in Thurn, proposed the adoption of a cartridge with a copper-jacketed bullet of his design. In 1883 he submitted cartridges of 7.5 and 8mm caliber to the Swiss

army that used copper jacketed bullets and were loaded with compressed

blackpowder. The next year the army had Schweizerische Industrie-Gesellschaft

(SIG) convert 130 Vetterli rifles to use the new cartridges for trial purposes.

While the cartridges showed promise it was obvious that the Vetterli rifles

were not strong enough and the new round-nose bulleted cartridges were

not safe to use in a tubular magazine.

I don't know if it's the water or the mountain air but for some reason 19th century Central European gun designers developed a fascination with the straight-pull bolt-action rifle. While the odd straight-pull design had popped up in Canada and the USA in the 1890s, it never achieved the acceptance it did among the Central Europeans, especially the Swiss and Austrians. Ferdinand Ritter von Mannlicher introduced his first straight-pull rifle around 1882 and perfected it by 1886, the same year it was adopted by the Austro-Hungarian empire. Whether or not Schmidt was influenced by Mannlicher (or vice versa) is up to conjecture, although they approached the problem of locking and manipulating the rifle's bolt in different ways. While Mannlicher used a tube sliding into the rear of the bolt and a wedge to lock it, Schmidt utilized a bolt handle that was attached to an actuating rod set in a channel on the right side of the receiver. This rod carried a lug which engaged a helical groove in the bolt sleeve that rotated it to unlock two opposed lugs from recesses in the receiver. Then the rod drew the bolt back to eject the empty case. Schmidt's straight-pull design allowed very rapid bolt manipulation, although it did not provide good initial extraction of the cartridge case. It also had the disadvantage of requiring a rather long, tubular receiver, although the design prevented dirt and debris from entering the action. In 1885 the Swiss army tested the Schmidt rifle against a design submitted

by SIG. But in 1886 everything came to a sudden halt when the French announced

the adoption of a smokeless powder cartridge and rifle, the 8x51R Mle.

1886 "Lebel."

The Swiss, already having a prototype cartridge and rifle, were in advance

of most other armies in this matter. Major Rubin and his design team at

the Thurn munitions factory quickly began work on a suitable smokeless

propellant. In the meanwhile, the army hurriedly adopted the Schmidt rifle,

on June 26, 1889, using a modification of Rubin's 7.5mm cartridge. But

it was not until 1891 that production got underway at the federal arsenal,

Eidgenossische Waffenfabrik in Bern, who would remain the sole manufacturer

of all Schmidt-Rubins used by the Swiss armed forces until 1958.

|

| Specifications--Infanterie Repetier Gewehr M1889

Caliber 7.5x53.5 Overall length 51.5 inches Barrel length 30.75 inches Weight 10.7 pounds Magazine detachable 12 round, charger loaded box Sights front: square blade rear: quadrant with U notch adj. from 300 to 2000 meters Bayonet sword style with 11.75 inch single edge blade |

|

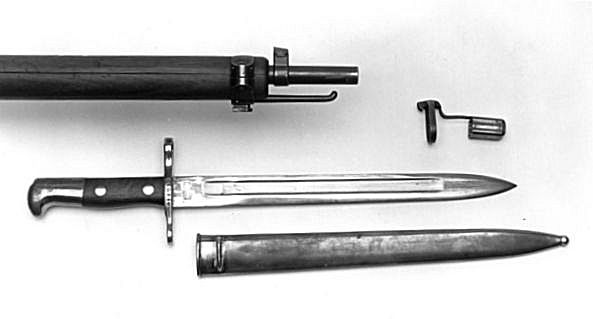

The new rifle, known as the Infanterie Repetier Gewehr 1889, was by our standards (or by anyone's!) overly long and heavy and its appearance was unique to say the least. The straight grip stock, which ran almost to the muzzle, had a oddly curved buttplate while a one-piece handguard ran from in front of the rear sight base to the muzzle band. There was one spring-retained barrel band and the muzzle/bayonet band, with its distinctively shaped stacking rod, was held by a pinch screw. The tubular receiver was 8.5 inches long, about 3 inches longer then a contemporary Mauser receiver, with a bolt handle that stuck out at a 90 degree angle and featured a two-piece composition bolt handle (later they were made from reddish plastic or aluminum). |

The distinctively shaped stacking rod was carried forward all the way through the K31 rifles. The M1889 bayonet stayed in service all the way through the Stgw. 57 rifle. (Photograph by James Walters) |

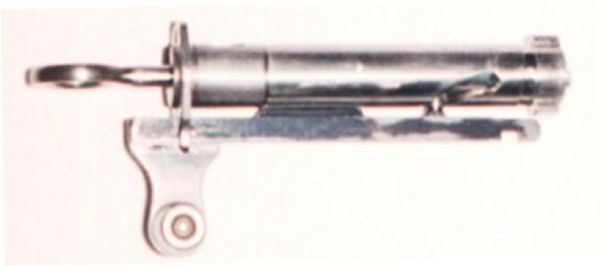

| The handle is part of the bolt actuating rod that moves within its

own tubular channel on the right side of the receiver. A ring shaped safety/cocking

piece was provided on the end of the bolt and was drawn back and rotated

clockwise to set the rifle on "safe." The ring could also be used to ease

the firing pin forward or recock the rifle for a second try at a recalcitrant

primer.

A 12-round removable box magazine was loaded through the top of the

open action by means of unique six-round chargers made from cardboard and

brass (later aluminum), while a bolt release lever is positioned directly

beneath the bolt handle.

The Swiss concern about the accuracy of the new rifle can best be seen when one removes the handguard. The barrel is completely free floating and that section of barrel under the muzzle band is encircled by an aluminum collar. This permitted the barrel to vibrate exactly the same for each shot by preventing pressure being put on the barrel either when it expanded from the heat of firing or if dampness caused the wood of the stock to swell. To my knowledge the only other military rifle to use this unique bedding system was the Finnish M28-30 Moisin-Nagant, another rifle that is famous for its accuracy. As with most things done it a hurry, the Gew. 1889 rifle had its problems, and extended field use showed several inherent weaknesses. The rear locking lugs allowed the bolt to compress under strain and the long bolt could not take much more pressure then the rather sedate M1890 cartridge generated. This became painfully apparent in 1895 when the Swiss attempted to improve the performance of the M1890 cartridge. In 1896 the Vogelsang/Rebholz modification was adopted which relocated the locking lugs to the front of the bolt sleeve, allowing the bolt and receiver to be made slightly shorter and providing improved locking. Manufacture of the improved Gewehr 1889/96 began in 1897 and continued until 1912. In 1897 a single-shot, short rifle with a 23-inch barrel, and using

a special reduced charge cartridge, was developed for military cadets.

Shortly afterwards a similar rifle, with a six-round magazine and using

standard ammunition, was adopted as the Kurzgewehr 1900, for cyclists,

artillery and fortress troops. In 1905 the first true Schmidt-Rubin carbine,

the Kavellerie-Karabiner 1905 with a 21.6 inch barrel, was adopted.

|

| Specifications -

Gewehr 1911

Karabiner 1911

Caliber ........................7.5x55.......................... Overall length 51.25 inches 43.4 inches Barrel length 30.75 inches 23 inches Weight 10 pounds 8.6 pounds Magazine ...detachable, 6 round charger loaded box.. Sights front: ..................square blade..................... rear: tangent adj. from 100 to 2000 meters tangent adj. from 100 to 1500 meters Bayonet ..sword style with 11.75 inch single edge blade.. |

|

By 1903 the Swiss had finally developed a suitable smokeless powder, and the new M90/03 cartridge pushed a 190-gr. copper-jacketed bullet to a muzzle velocity of 2050 fps. In 1911 this was updated with a 174-gr. boattail spitzer bullet that had a larger .308 diameter and a muzzle velocity of 2640 fps. To prevent it being inadvertently fired in older rifles the M1911's

cartridge case was lengthened to 55mm. The Swiss also took this opportunity

to update the Schmidt-Rubin once again and the resulting Gewehr 1911 infantry

rifle and Karabiner 1911 carbine used stronger receivers, new tangent rear

sights and pistol grip stocks. Several lightening holes were drilled in

the receiver and this, along with a six-shot magazine, lightened it by

more then a half pound.

A redesigned magazine follower held the bolt open after the last shot had been fired. Older rifles and carbines deemed suitable for conversion were updated to Gew. 1911 specs with new barrels, sights, six-shot magazines and a pistol grip inletted into the stock. The most common of these conversions was the Gewehr 1889/96 rifle, which was redesignated the Gewehr 96/11. |

|

| In spite of their clumsy appearance the Schmidt-Rubins were very pleasant

rifles to shoot. The action worked smoothly, fed cartridges easily and

had a very crisp trigger pull. Magazines were fast and easy to charger

load, the sights provided an excellent sight picture while the rifle's

weight kept recoil down to a very controllable level.

Traditional Swiss quality of manufacture, and the excellent issue ammunition, allowed the Swiss soldier to live up to the traditions of William Tell and he continued to be known for his marksmanship. The only real complaint voiced by the rank and file about the new arms was the inordinate length of the infantry rifle. The lessons of World War 1 had shown that the traditional long rifle

had many shortcomings, and this was not lost upon the Swiss. In fact, the

Kar. 1911 carbine (in reality a short rifle with a 23-inch barrel) eventually

became the preferred weapon and production of the infantry rifle was ended

in 1919 while that of carbines continued until 1933.

Between 1930-32 the Swiss attempted once again to update the Schmidt-Rubin

with a radically redesigned straight-pull action. The resulting Karabiner

1931's most important change was the relocation of the locking lugs to

the bolt head where they locked into the receiver ring. This resulted in

a receiver that was not only much stronger but was 2.4 inches shorter then

the Gew. 1911's and while the Kar. 1931 had a longer barrel, its overall

length was only 4mm greater then the Kar. 1911 carbine. The bolt

actuating rod has a flat cross section and the front sight was protected

by a set of sturdy "ears."

|

| Specifications--Karabiner 1931

Caliber 7.5x55 Overall length 43.6 inches Barrel length 25.7 inches Weight 8.8 pounds Magazine detachable, 6 round charger loaded box Sights front: square blade rear: tangent adj. from 100 to 1500 meters Bayonet sword style with 11.75 inch single edge blade |

|

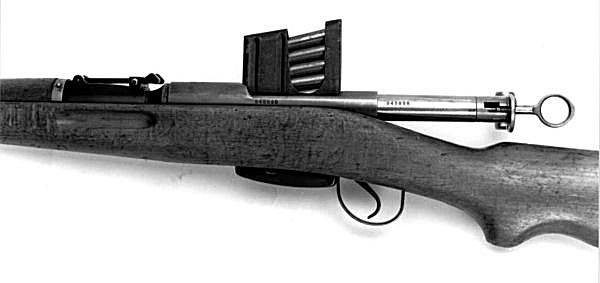

Production of the Kar. 1931 began in 1933 and continued until 1958, eventually replacing all earlier models in service with Swiss active duty units and reserves and it was only in the last decade that it was finally declared obsolete for reservists. The Kar. 1931 quickly earned a reputation as the most accurate of the Schmidt-Rubin series and it served as the basis for several sniper rifles (Gew. 1931/42, Gew. 1931/43 and Gew. 1955). A little known bit of firearms history trivia is that only one other sovereign nation's armed forces were equipped with Schmidt-Rubins. In the 1930s Eidgenossische Waffenfabrik produced a special run of 100 Kar. 1931s for the Vatican's famed Swiss Guard ("Papstilche Schweizergarde"). They were also produced for commercial sale to Swiss citizens who wished to purchase their own rifles (in addition to the government supplied one in the bedroom closet!), and served as the basis for a series of target rifles ("Prazisionskarabiner") made for UIT and Biathlon shooting. |

|

|

Kar. 1931 actions were used to produce sporting rifles by such well known Swiss gunmakers as Hammerli and Grunig & Elmiger, as well as smaller gunsmiths. Many of these were chambered for more popular sporting cartridges. Upon learning that Century International Arms had recently received a shipment of Karabiner 1931s from somewhere in the Alps, I requested one to test. While Century's catalog listed their condition as "good," the Kar. 1911 I received was mechanically perfect with a pristine bore, about 90% metal finish and a beech stock marred by only minor dings and scratches. The quality of manufacture and the fit of parts were excellent and it operated with an oiled smoothness that was a joy to behold. It was built like a...well, like a Swiss watch! Before shooting the rifle I stripped it down to clean and inspect it (a practice that should be followed with ALL surplus firearms!). Underneath the buttplate discovered a plastic card bearing the name and unit number of the last solider it had been issued to: "Mw.Kpl. Dannecker Hch.-Schw. Fus. Kp. IV/80-Reherobelstr. 24-St. Gallen". An absolutely fascinating bit of personalized history if I say so myself! Up until a decade ago Schmidt-Rubins were common on the U.S. surplus market and surplus 7.5x55 ammunition was easy to come by. Well nowadays they aren't and it isn't! At present the only source of shootable 7.5 Swiss ammunition in the USA is that made by Norma. So I contacted Norma's American distributor, Dynamit Nobel-RWS, Inc., for a couple of boxes of their 7.5x55 cartridges loaded with a 180-gr. soft-point bullet at a velocity of 2651 fps--very close to the specs of the Swiss issue M1911 cartridge. Test firing of the Karabiner 1931 was conducted on my gun club's 100-yard

range. While the original style charger looked odd and felt flimsy, loading

the magazine with it was quick and easy. The trigger had the usual two-stage

pull but once the slack was taken up, the letoff was one of the crispest

I've ever felt on a military rifle while the excellent sights provided

a sharp, clear sight picture.

|

All Schmidt-Rubins used an unusual six-round charger, at first made of cardboard and brass and later of aluminum. Norma is about the only regular source of 7.5x55 ammo. (Photograph by James Walters) |

| In all, I fired eight 5-shot groups, the smallest of which was a very

pleasing 1 7/8 inches, while the remainder all came in at under 3 inches!

You can say that the Schmidt-Rubin is old fashioned, and you can say that

it's funny looking--but don't ever say it isn't accurate! The rifle functioned

perfectly, I did not experience a single problem chambering or ejecting

any of the 40 rounds of Norma 7.5x55 ammunition I fired in my two-hour

shooting session.

It has often been claimed, possibly with some justification, that the

only reason the Swiss stuck with the Schmidt-Rubin straight-pull rifle

for so long was that its deficiencies were never brought to light by the

harsh realities of combat.

But in the matter of small arms the Swiss have long held a fascination for complicated designs. Besides the Gew. 1889 they were the first to embrace the complicated Parabellum (Luger) pistol. When simple blowback submachine guns were already available they instead took into service the ridiculously intricate Furrer MP41/44. Their MG25 and MG51 light machine guns were overly complex weapons at a time when simpler designs were already on the market. Finally their Stgw. 57 assault rifle--while one of the finest military

rifles of this

According to reports, the Swiss army's new Stgw. 90 rifle is more expensive to produce than other, more proven designs. This proclivity for adopting native designs, despite their complexity and cost, seems to be ingrained in the Swiss character. They are justifiably proud of their ability to produce finely made arms and in this era of mass production such old fashioned pride in craftsmanship is a unique, and pleasant, thing to see. And- just perhaps--it gives the Swiss infantryman a good feeling to know that his rifle wasn't produced by the lowest bidder. For further information:

|

|

Bibliography

(Note: the bibliography did not appear in the originalarticle, but is provided here for the readers convenience) Barnes, Frank C. CARTRIDGES OF THE WORLD, 7th Edition. Northbrook, IL: DBI Books, Inc., 1993.. Hogg, Ian and Weeks, John. MILITARY SMALL ARMS OF THE 20th CENTURY. Northbrook, IL: DBI Books, Inc., 1985. Janzen, Jerry. BAYONETS FROM JANZEN'S NOTEBOOK. Broken Arrow, OK: Cedar Ridge Publications, 1991. Smith, Joseph. E. SMALL ARMS OF THE WORLD, 9th Edition. Harrisburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1969. Smith, W.H.B. and Smith, Joseph. BOOK OF RIFLES. Harisburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1972. Tanner, Hans. SWISS MILITARY RIFLES. Published in Guns of the World. New York: Bonanza Books, Inc., 1977. Walter, John. RIFLES OF THE WORLD. Northbrook, IL: DBI Books, Inc., 1993. Webster, Donald B. MILITARY BOLT ACTION RIFLES 1841-1918. Alexandria Bay, NY: Museum Restoration Service, 1993.

|

Back to the Schmidt-Rubin Page